Let’s talk about enshittification – and yes, this is an actual term! Do you notice your favourite products, platforms or services steadily deteriorate in quality over time? See articles about services and marketplaces charging for functionality you otherwise used for free? Well, more likely than not, it’s a symptom of these places turning to complete and utter rubbish!

Today, we explore the slow burn process of manufacturers, tech companies and other businesses appealing to everyone in different ways, then extracting value from them. In other words, maximising short term gain at the cost of long term sustainability.

What exactly is enshittification anyway?

Enshittification, crapification, or “poopification” (as we will call it from now on) is where companies make decisions which result in making their products and services worse for their customers. Usually, it is a gradual process with a focus of maximising profits from customers, advertisers and suppliers. But eventually, these groups grow dissatisfied to the point of taking their respective customs elsewhere.

Cory Doctorow first used the term in a November 2022 blog post, where he explained how people started leaving Facebook and Twitter en masse. He also used the term ‘platform decay’ to illustrate the same concept. Then, he released another blog post in January 2023, further elaborating on the poopification concept. There, he describes how companies make platforms flourish, then exploit users, advertisers and suppliers for profit, and finally let the platforms wither into irrelevance.

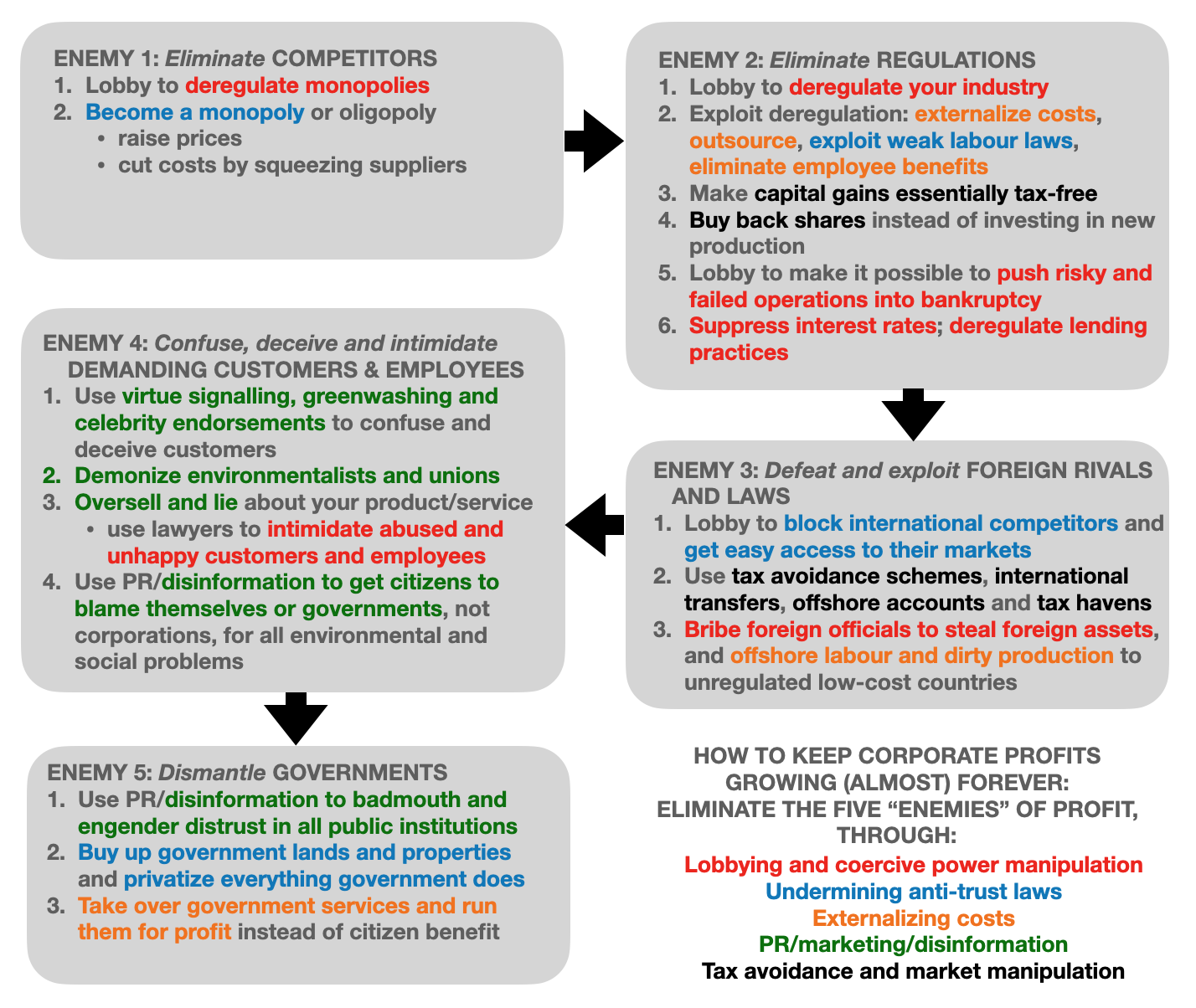

In a May 2024 post, Dave Pollard further expands upon Cory Doctorow’s articles about poopification. He illustrates how it is the culmination of decades of unregulated capitalism. According to Pollard, businesses engage in activities with the goal to maximise profits. He identified five key areas which keep the businesses in check, and how they work to undermine, and eliminate these as if they are obstacles. These are: competitive markets, domestic laws and regulations, overseas rivals and laws/regulations, consumer groups and unions, and Governments.

How poopification works

- Firstly, a business launches a new platform or marketplace. It leverages products and services as loss leaders to attract users to the new platform or marketplace.

- Then, the business encourages these users to purchase goods and services from them. One approach is to stock items which customers can’t easily find elsewhere.

- Once it sufficiently locks in a critical mass of customers to the platform/marketplace, the business then uses its customer base as a loss leader to attract suppliers and advertisers.

- Afterwards, it then exploits the suppliers to accrue the value and profits in order to keep advertisers satisfied.

- Then, the business leverages the platform/marketplace to maximise profits for itself, along with shareholders and venture capitalists.

- Finally, the business goes into stagnation and decline, as people and organisations abandon the platform. Particularly, advertisers will search for other loss leaders in markets. Eventually, it withers and dies, or another business buys the failing platform for itself.

Does this only happen to platforms?

Sadly, no. While we see this often with online marketplaces and social media platforms, anything can fall victim to poopification. From everyday items such as food and drinks, tech gadgets and furniture, to services such as healthcare and public transport. Often, there is the tendency among organisations to succumb to greed and the allure of ever greater profits. And as a result, they – along with the environment as a whole – become unsustainable.

In fact, we would argue that planned obsolescence often goes hand-in-had with poopification. Basically, manufacturers transitioned from building products to last, to extracting value from expensive repairs and new product sales. By doing this, they can maximise profits for themselves and their investors. Consequently, planned obsolescence and poopification contribute to a ‘throwaway society’.

But what happens when free and open source software (of all things!) fall victim to poopification, too? What if maintainers of Linux distros engage in the same anti-user practices Microsoft does with its proprietary Windows OS? Here, Nick from The Linux Experiment demonstrates what might happen when the concept applies to a Linux distro…

What if it happens to repair cafes?

But what happens when repair cafes like our own Reyt Repair workshops succumb to poopification? Well, imagine an alternate universe, where Gareth transforms them into a global enterprise. One where our repair cafes pop up all over the world, and people can help fix each other’s things. Even in Antartica – because there are humans living in small colonies there as well. Can’t have them go without repair services, after all!

And then, one day he starts to turn to the dark side. He cannot resist the temptation of the massive profits Big Tech earn year after year any longer. Slowly but surely, he enacts measures to extract profits from these enterprises. He transitions from being an awesome pro-community fix-it-upper, to an evil corporate overlord. Gradually, piece by painful piece, he turns Reyt Repair – and other enterprises he runs – into the exact same entities as the manufacturers in the real world. Entities which engage in the very practices he founded these groups to fight against.

So how would Gareth do it all in this alternate universe? Let’s go over some of the different ways he would enshittify our services, the workshops and…well, everything else!

How Reyt Repair could go through poopification

Basically, the key part in the poopification of our services is in doing so in subtle, gradual steps. If he does it too quickly, then customers will go elsewhere, and our services will suffer as a result. So, let’s go through the steps in the poopification process, and cover some of the ways in how they work in practice. They may not happen in the exact order we list here, but they illustrate how a repair cafe goes from serving the community to serving the “mighty pound sterling”!

Step 1: Attracting customers and volunteers

Gareth needs ways to encourage everyone in Sheffield and beyond to take their items into the Reyt Repair for repairs, and to devote spare time to help out with repairs. Just like in the real world, they reside in a small room inside Abbeyfield Park House. So, how to expand beyond the busy main roads in Pitsmoor?

Well, we can send our flyers all over the city to start with! Basically, flyers help inform people about our work, and how they can help us repair everyday items in the community. Additionally, we can augment these with some local ads to really get our social enterprises out into the collective consciousness!

Step 2: Establishing the enterprises

Next, he needs to build up an empire, where he reaches out and sets up repair shops to the rest of the UK. Bonus points if he gains a presence across the rest of the world! Initially, teams of volunteers can create articles and materials which garner interest in our work.

In the real world, I predominantly take on the responsibility of writing articles for this website. Usually, I focus on quality over quantity in making them informative, insightful and/or humourous. But in this scenario, I can only produce so much content without veering straight into clickbait territory! And so, I need all the help I can get! (In fact, perhaps I should try dabbling in AI tools like chatGPT. After all, it might prove useful for augmenting my work in writing interesting articles for us all…)

To expand the network, volunteers in other parts of the country can set up new repair cafes and shops under Gareth’s family of social enterprises. In this way, we can help serve communities across the UK and beyond.

Step 3: Monetising everything

Once Gareth reaches a critical mass of volunteers, customers and online followers who all want to be part of his burgeoning repairs empire, he needs ways to really start raking in the cash. Because after all, all this work in growing his empire costed him valuable money. This is the point where Gareth sells the souls of Reyt Repair and other enterprises he operates to the devil!

Initially, he could put the most interesting articles on this site behind a subscription paywall, where readers pay a small monthly fee to access these articles. Another way to make money is to source cheap, questionable quality components for repairs. Bonus points if he finds parts no other repair cafes have! This ensures customers will keep coming back to Gareth’s repair shops.

Step 4: Enlisting the services of suppliers

Without spare parts, Gareth’s repairs empire can’t fix all kinds of everyday items. To ensure that his repair shops always have the necessary parts, he can do deals with various manufacturers. These manufacturers then supply the spare parts to his repair shops.

After a time of gaining customer confidence, he can then start to reduce the quality and cost of the spares to boost his operating profit. Usually, this entails specifying cheaper and less durable materials, particularly for critical components in the parts to accelerate wear and tear. Naturally, he will proceed cautiously, only subtly reducing quality over many months to maximise thee time it takes until the customers begin to notice!

Step 5: Acquiring venture capital

To keep his empire going, Gareth would reach out to investors and venture capitalists. He would enter discussions with them to strike deals, where they offer capital upfront, in exchange for a share of the profits from his repair empire. To further sweeten the deal, he would further monetise the site(s) and the repairs services – which means, you guessed it, more enshittification. By now, he notices that the premium subscription services for the super-interesting articles on this site are wildly popular. So he decides to roll it out across the rest of the websites under his wing.

He can also, at this point, choose to go public with his empire on stock markets across the world. This allows investors to buy stocks and shares in his conglomerate. It also means one more group of people he needs to keep on his side – but hey, such is business! These injections of funding would allow him to further sustain the business – oh, and buy more beachfront properties (and shiny yachts!), because why not?!

Step 6: Selling out to the advertisers

By this time, the volunteers churn out all sorts of interesting and insightful articles for Gareth’s repair empire. They busily maintain a strong presence on social media. But all this effort only goes so far in sustaining a strong mindshare in the world at large. So now, he needs to go beyond the local papers and go not just national, but international!

And what this entails, is enlisting the help of marketing companies to really get the brands out there! There are ad spaces for television, radio, billboards…oh, and especially in apps and online, too. Speaking of online in particular, Gareth decides to wring more value out of the websites under his empire by placing ads throughout the site. Sure, this would open readers up the risks of malware and scams miscreants place through ad networks. But hey! By buying a monthly subscription for a small fee, they can remove ads, as well as browse all the super interesting articles to their heart’s content.

Step 7: Accruing all the value for oneself (and shareholders & venture capitalists!)

Here is where Gareth starts to work on keeping all the value he accrued from his empire for himself – along with all of the shareholders and venture capitalists he attracted along the way! Essentially, he would do all of the measures we covered earlier – but crank it up to eleven! In fact, he realises technology evolves to such an extent, he would just fully automate all of the repair jobs and content creation using a mixture of robotics and AI tools. No volunteers and staff necessary any more!

While Gareth goes about it, perhaps he’ll use the extraordinary wealth he built up over the years to entertain himself and fellow billionaires. For example, he could start a mission to enter space – if the likes of Jeff Bezos and Richard Branson can send rockets into space, then so can Gareth!

Or, perhaps he could explore the depths of the oceans in a submarine. Who knows? If he really fancies a challenge, Gareth could try building an underwater city deep in the oceans. All with its own public services and means of producing everything cities need to thrive!

Step 8: Withering on the vine at the end of it all

Eventually, Gareth pushes his efforts in maximising profits from his repairs empire too far. And all the volunteers, the customer base, and everyone else reach the point of not taking all the poopification any more. At this point, some of them start setting up their own local repair cafes and workshops to break free from the network lock-in. And when these workshops start thriving, customers simply take their items there for repairs instead. Consequently, Gareth’s repairs empire experiences a gradual decline in relevance and sustainability. One of the following would happen at this stage:

- His enterprises would still operate as much smaller businesses.

- He would sell them off to another business, which would operate them as part of its portfolio.

- Worst case, the enterprises would simply close down for good.

Now, Gareth might try to buy up all of the fledging repair shops he possibly can. However, at this point, it’s a case of delaying the inevitable. People who feel his excessive profiteering costs him all the trust and goodwill he spent so much time and effort building up, do not easily forgive and forget. And, once they turn away from his empire, they will not willingly return. In fact, they may even revert back to discarding broken items and only buying new ones out of sheer disillusionment.

Summarising poopification

In conclusion, poopification is the insidious creep of sacrificing long-term quality and sustainability for maximum short-term profits. Ultimately, the resultant decay of products and services benefits no-one in society. It has a detrimental impact on the environment, with many poor quality products needlessly going to waste. And so, we all deserve better, repairable and sustainable products and services.

We used our own workshops as an example to illustrate how poopfication subverts efforts to help communities and the environment. Because if it creeps into our work in real life, then it will negatively affect every other existing community repair group and social enterprise. So let’s all keep calm, keep on fixing, and support each other and our communities!